From the white void, a black speck emerges. No more than a few pixels wide at first, this blob drifts closer and closer to us. As it slowly nears, the blob becomes a being whose legs and arms can be seen swaying in the wind, whose blustery din acts as this image’s soundtrack. Then, at the point when it is finally obvious that the blob is a human marching through a wind-swept plain, the man collapses to the ground and the shot ends.

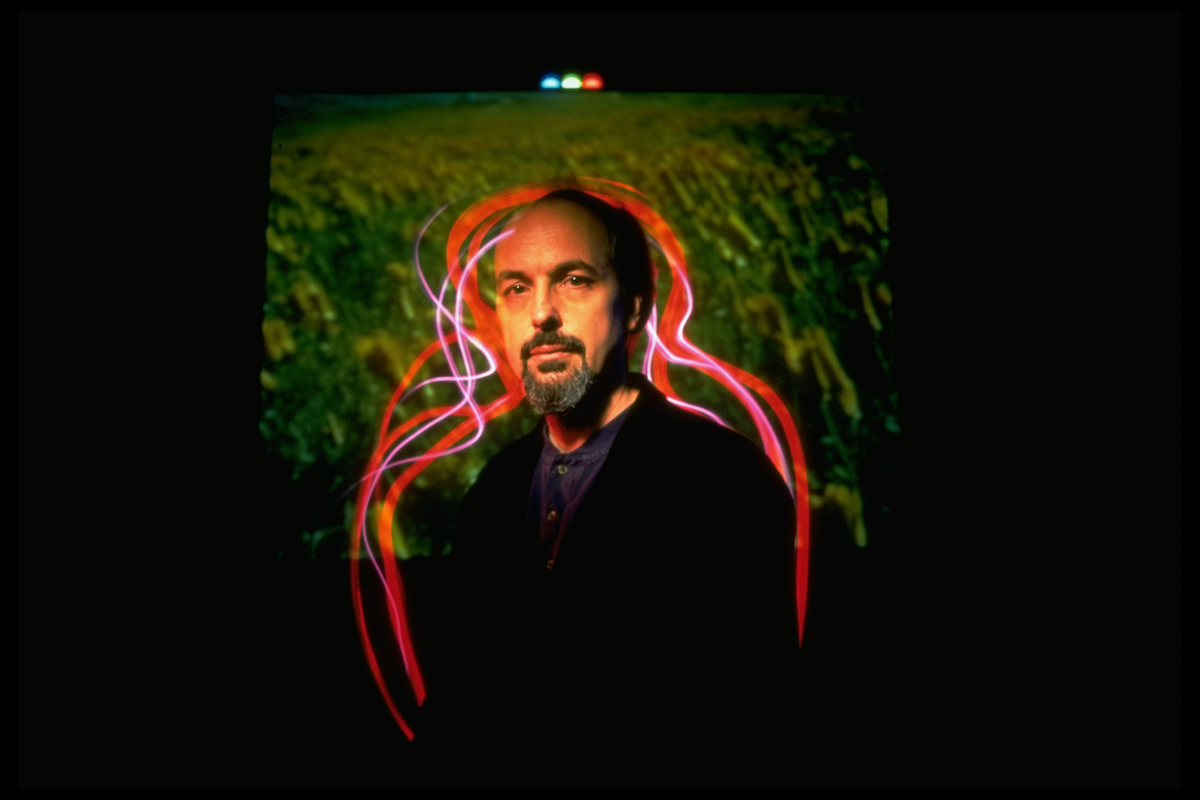

This three-minute-long take appears in the 1979 video Chott el-Djerid (A Portrait in Light and Heat), an early masterpiece from Bill Viola, who died this past weekend at 73. To make the video, Viola journeyed to remote locales—snow-laden prairies of the US and Canada, a heat-warped desert in Tunisia—and captured the sights seen, rarely moving his camera at all. He’d sometimes spend days trying to get a shot, waiting until the weather aligned with the image he desired.

Viola wrote that his goal, in braving what he said felt like “the end of the world,” was to reach “the edge”—the place where perception breaks down and life starts to look very different. “It is like some huge mirror for your mind,” Viola wrote, adding, “Inside becomes outside. You can see what you are.”

The irony is that in Chott el-Djerid, and in many other works by Viola, there is not always much to see. Long takes of unsettled waters and shadowy figures are constants in Viola’s oeuvre. Abstract images composed of indefinable light and inky darkness recur as well, even in his later multiscreen video installations, which are more narrative-driven.

But there was always more than what was portrayed on screen in Viola’s works, which forced viewers to see beyond the exterior world. He brought art to its limits, showing that the act of looking at an object requires gazing inward, too.

He was not alone in producing perception-bending experiments using video. During the 1970s, artists a generation Viola’s senior, such as Joan Jonas and Vito Acconci, had already harnessed filmed themselves live and had onlookers reflect on these images in real time. Jonas and Acconci produced tapes that were icy and clearly very conceptual—an entirely different sensibility than what is obvious in Viola’s early works. His tapes could be categorized as capital-R Romantic in the same way as Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings, since Viola’s videos are also about the sublime.

Many of Viola’s works inspire awe and terror, in particular the ones that allude to the artist’s own near-death experience. When he was 6, Viola was vacationing with his family when he almost drowned. What should’ve been the scariest moment of his life ended up becoming the most beautiful one: he spoke in interviews of feeling as though he had reached “heaven.”

In The Reflecting Pool (1977–79), one of Viola’s earliest works featuring aquatic imagery, the clothed artist walks up to a pool and jumps. But before he can complete his cannonball, his body comes to a halt, suspended mid-air above water that continues to ripple. Gradually, Viola disappears, only to emerge from the water, this time in the nude. He has been physically transformed by being beneath the surface, which remains invisible to viewers.

Viola’s work from the 1980s onward sought to inspire a similar spiritual metamorphosis in his viewers. His 1983 installation Room for St. John of the Cross was a breakthrough, merging sculptural elements and video footage to obliquely recreate the nine-month imprisonment of the titular 16th-century Spanish Catholic saint. When the Museum of Modern Art presented it, a small cubicle with a video monitor and a jug was set before a larger projection of an unbroken shot of a mountain. Throughout the room played audio of roaring wind.

Art historian Jean-Christophe Ammann once wrote that he was so moved by the installation, he no longer wanted to visit a Frank Stella show that was also on view at MoMA at the same time. Instead, Ammann said, he returned to his hotel room, “carrying in my heart the trembling treeleaves” heard within.

What inspired such a reaction? One can only speculate, as Ammann did not specify. But it probably had something to do with the way that Viola slowed things down, making viewers observe the passage of time, as St. John did when he inhabited a cramped, windowless cell that was so tiny, he could not even stand upright. Time is not something that can be seen. It can, however, be felt.

Religious content became a fixture in Viola’s late-career work, which drew on his studies of Christianity, Sufism, and Zen Buddhism. As these works exploded across multiple screens, they unfurled epic cycles having to do with birth, life, death, and the afterlife. Going Forth by Day (2002), the one I wrote my undergraduate thesis on, features a figure moving through a uterus-like pool, a lamentation-like gathering for a dying man, and an inexplicable resurrection (involving water, naturally). Works like that one tend to be seen as religious experiences or spiritualist drivel. Critic Adrian Searle once dinged Viola’s late-career works for devolving into “theatre and spectacle.” I always felt a twinge of embarrassment every time I had to admit that Going Forth by Day made me cry.

It seemed to critics like Searle that Viola had moved away from the concerns that guided works like Chott el-Djerid, producing extravagant pieces that were big, loud, expensive, and obvious. I’d argue otherwise. Viola had merely continued his project of depicting the undepictable. His new reference points—Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel, Jacopo da Pontormo’s Carmignano Visitation, and the like—were equally engaged in the difficult project of representing that which cannot be seen, be it death or a gust of wind. Viola had simply used a camera instead of paint.

Even though he was deeply engaged with the Western art-historical canon, Viola frequently spoke of using a video camera to represent things that had never before been represented. In the case of Chott el-Djerid, he pointed his camera at some of the hottest stretches of desert in Tunisia, areas that are known to produce hallucinations because of their extreme temperatures and vacant settings. He estimated that, as he peered into his lens, he could not see around 90 percent of the desert while shooting. An “eye without a mind,” his lens was able to capture “even less of this big world than what you’re trying to see all at once,” he once said. “And that was the way to get into the mirages!”

A basic description of Chott el-Djerid might make this video seem like a bunch of heat-distorted shots of sand, but this work is more than what’s shown onscreen. It’s a video that succeeds in feeling like a journey to a place unknowable to rational eyes. Viola said he was “cutting out an enormous amount of what I was seeing and narrowing it down to this tiny little portal. Then, suddenly, when you do that, the mirages are completely here; you’re in their world.”